Dual Citizenship and Border Patrol: Picturing Tijuana's Contested, Transnational Water

page 1

The two rivers that serve the city of Tijuana—the inbound Colorado and the outbound Tijuana—are two heavily litigated, politically contentious, courageously border-defying bodies of water. Artificially yoked by a 118-mile long aqueduct that spans northern Baja's vast desert, these two conjoined entities labor to hydrate this rapidly and perilously expanding metropolis. At the jagged crux between California and Arizona, the Colorado River crosses into Mexico with only 10% of its total flow still intact. By the time it reaches Tijuana, just 5% of that 10% remains. Once this water has circulated through hundreds of thousands of homes and industries, the Tijuana River routes it northward to re-cross the border and enter an estuary near San Diego. From Yuma to San Ysidro, this intensively mediated, twice border-crossing transnational flow has never found favor with the United States, for the U.S. has long been loath to relinquish the water that is historically destined for Mexico—but it is even more loath to see that same water return.

page 2

Despite the miniscule portion of the Colorado River assigned to Tijuana, the city nonetheless depends upon it for 95% of its water. Tijuana's aqueduct delivers it to a picturesque reservoir just east of town—then onward it flows within a gigantic blue pipe to a mountaintop treatment plant that (to the best of its abilities) makes this water serviceable for municipal use. This plant (and all of Tijuana's water infrastructure) is operated by the Comisión Estatal de Servicios Públicos de Tijuana, also known as CESPT. The treated water is then shunted to an army of hilltop cisterns, for extensive pumping and gravity flow is the principal delivery mode for this very hilly city.

page 3

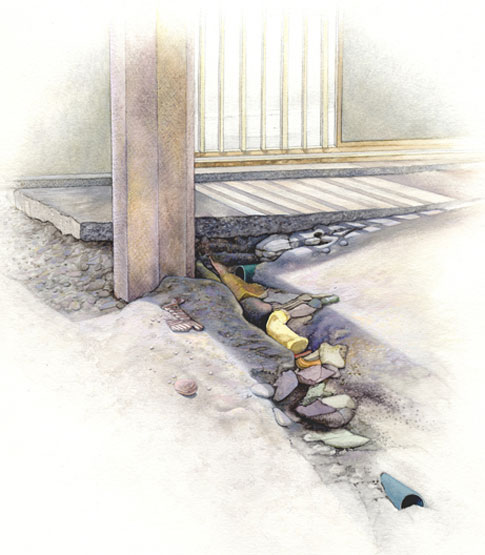

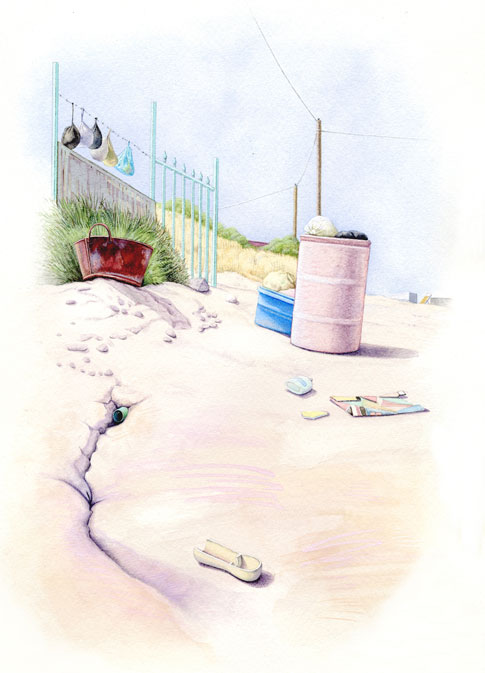

One of these lofty cisterns overlooks Colonia La Morita—a hastily constructed community of both legal and illegal settlements, created in response to a hurried demand for workers for the Maquiladoras—the NAFTA-fueled, foreign-owned factories that now pepper the U.S.-Mexico border by the thousands. Virtually no one in La Morita was born in Tijuana, and virtually all of the homes were built by hand. CESPT and La Morita's homebuilders have a complex and nuanced relationship—a flexible system of contingency and compromise for an overburdened municipal agency and a community of cash-strapped migrants.1 CESPT is legally and ethically obliged to deliver water to residents, for example, so long as a property is legally owned—though sometimes water gets to illegal settlements as well. CESPT charges for water, but cannot (in good faith and good political will) shut it off if someone is unable to pay. The official pipeline also stops at the fence line, so residents must find ways to get it into their houses, which accounts for the assortment of improvisational materials and techniques (usually mazes of PVC pipes) that decorate individual homes and yards.

page 4

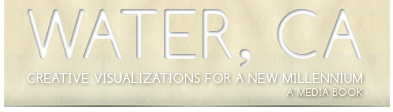

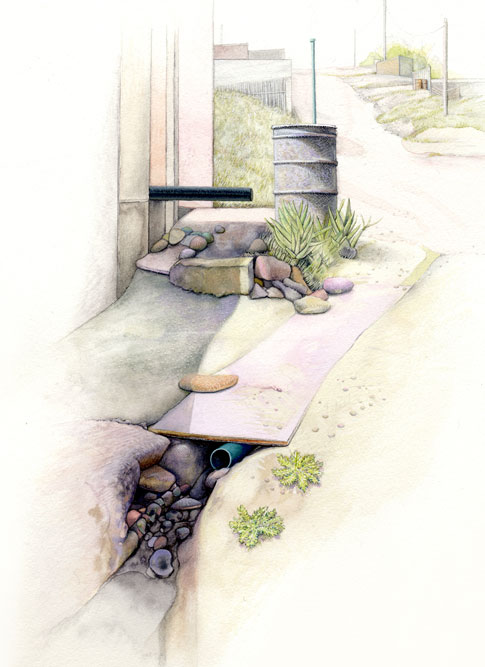

Water came to La Morita in the mid-nineties, but CESPT installed the sewers much more recently. The original sewer infrastructure included a homemade pastiche of street-side protruding pipes of varied lengths and diameters—devices that would often (and unexpectedly) disgorge their contents at the feet of unsuspecting passersby. These systems of cylindrical conduits and moist, meandering swales—environmentally problematic though they were—created a dribbling, oozing landscape perforated with metaphorical fecundity. These contraptions of disgorgement and receptivity, of freely flowing household fluids, rutted the roads and collected in fetid and fertile pools. These streetscapes, however, were created as a result of migratory growth rather than natural growth, as Tijuana's birthrates are actually on the decline. Nurtured as it was by NAFTA and credit-crazed U.S. consumers, this situation was begot by a sexless reproduction—an economically generated population explosion. My paintings, nevertheless, relish the ripe and expectant erotic appeal intrinsic to these resolutely functional forms.

With La Morita's new sewers, CESPT is now attempting to remedy a situation undeniably undesirable to human health. The effluent that once dribbled from homes into the nearby Arroyo Florido—which in turn episodically flushed into the Tijuana River—will soon be diverted to a new sewage treatment plant funded by the Mexican Government and a Japanese bank. Indeed, thousands of fugitive flows like La Morita's are now marked for eventual capture, and this new plant (among others) will be entrusted with this effluent's incarceration, rehabilitation, and subsequent release.

The Tijuana River, lined with concrete for its final 13 Mexican miles, is home base for this treated wastewater, alongside rainwater and the contents of renegade flows unencumbered by sewers.2 At its border crossing, the river's volume can vary tremendously: depending on the weather, a modest trickle can swiftly swell into a multi-million gallon deluge. The U.S. balks at this water's return, of course—laden as it is with the troubling and often industrial-strength residuum of an economic fecundity that its own country had fertilized in the first place.

The U.S. does allow the river to flow, however, under specific legal conditions. It must be raining (for one) and the volume must exceed the capacity that a border-side Mexican pump station can handle.3 Once in the U.S., this repatriated water must undergo processing by an international sewage plant before final release to the Pacific. This international plant can't retrieve all of it, though; scofflaw flows sometimes elude capture and escape into the Tijuana River estuary or onto U.S. beaches. That Mexican pump station has a big job too: shunting up to 30 million gallons a day to the shimmering, noxious Punta Bandera treatment plant—an enormous, unexpectedly lovely lake of shit that overlooks the ocean just west of Tijuana. Punta Bandera treats its effluent to the best of its abilities, and then onward it flows onto Mexican beaches.

For their part, the Mexican Government's stated goal is to stem this tide of uncontrollable aqueous immigration—to stop this flow in its tracks with high technology tactics. The new sewage plants, says CESPT, will treat the city's effluent to environmentally acceptable standards, and then redirect all of it—just before crossing—to an ocean outfall pipe a thousand meters off the Mexican coast.4 There's also another, longer-range plan for this water: instead of relinquishing it to an antagonistic northern neighbor or the long-suffering Pacific, CESPT plans to use it to irrigate local parks, universities, and open spaces. Greening Tijuana with recycled water would certainly refresh a city of too few verdant spaces, and could also help to replenish the city's beleaguered aquifer and depleted wells. An aquifer recharge program for Tijuana could also bring some relief to the similarly beleaguered Colorado River, which must support the agricultural and municipal demands of five U.S. states and multiple megalopoli (including Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and San Diego) as well as all of the cities of northern Baja and the currently imperiled Mexicali Valley.5

page 5

With infrastructure that requires no costly funding, Tijuana's informal communities can (and in some cases do) recycle their water and replenish their aquifer now. In an illustration I made for the artists' collective SIMPARCH, a neighborhood of "spontaneous architects" deploys simple and inexpensive technologies that largely free it from corporate and municipal dependency. This community uses its household effluent to irrigate garden plots, and makes its own fertilizer with composting toilets. With these toilets, residents separate their water from waste at the outset—transforming both into useful commodities and circumventing the need for sewage treatment. Their rooftop distillation devices, furthermore, turn any effluent into perfectly drinkable water by passive solar power alone. In this conjectural drawing, SIMPARCH's fantasy autonomous community cheerfully and blithely ignores a backdrop of mountaintop Maquiladoras—looming corporate entities, smug in their assurance that they alone control the Cosmos like the gods of Mount Olympus.

page 6

Tijuana's communities, in fact, have long practiced strategies of economic autonomy with gray-water gardens, neighborhood flea markets, and spontaneous activities of sharing and barter. Activists and urban planners have devised low-tech solutions for replenishing Tijuana's aquifer and reducing river and estuary pollution and sediment as well. Oscar Romo's cobblestone-like "permeable pavers", most notably, reduce the run-off from dirt roads on steep hillside Colonias—redirecting that water straight down. The city's EcoParque, similarly, affordably treats the wastewater from 1,200 hillside households and uses it to irrigate a lush 15-acre public park.

Scholars like Ismael Barajas and Stephen Mumme say that watersheds are notorious for disregarding established political and administrative jurisdictions, and that watershed management is governmentally demanding and politically messy. They also say, however, that watersheds can be catalysts for binational understanding and collaboration as well.6 Though nations tend to be singularly protective of their own interests and sovereignty, individual community builders, activists, and artists tend to take a more conflated view in often modest and metaphorical ways. They work alongside these audaciously defiant watersheds, busying themselves by trenching and diverting these vast, nomadic trajectories, unearthing and irrigating all manner of compelling and consequential insights along the way.

footnotes

| 1 | I pieced together the details of this adaptive system by interviewing both CESPT officials and La Morita residents in January 2009. |

| 2 | Camp Dresser & McKee Inc., Transboundary Environmental Assessment for Expansion of Wastewater Collection System for Tijuana River Basin Area, (Research Report prepared for CESPT and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2008) 2-6 |

| 3 | Camp Dresser & McKee, 3-5 |

| 4 | Agustín Rojas Arrieta, CESPT's Public Relations Director, in an interview December 2008. |

| 5 | The concrete lining of California's All-American Canal (underway at the time of this writing) will severely compromise the agriculture of the Mexicali Valley by depleting its wells and its aquifer. This border-side canal was constructed in the 1930's to divert Colorado River water to California agriculture and cities. Its unlined construction (until now) permitted water to seep from it, stealthily cross the border, and filter into the Mexicali Valley aquifer. |

| 6 | Stephen P. Mumme and Ismael Aguilar Barajas, Managing Border Water to the Year 2020: The Challenge of Sustainable Development, (The U.S.-Mexican Border Environment: Southwest Center for Environmental Research, 1999) 85-86 |

RELATED PLACES Colorado River, Mexicali, Calexico